SOCIOLOGISTS have argued long and hard about the cultural revolution called The Swinging Sixties.

Christopher Booker, for example, claimed many Brits were unable to cope with the post-war economic boom and by 1967 ‘they felt that in the previous 10 years they had gone through a shattering experience’.

Bernard Levin said ‘the stones beneath Britain’s feet had shifted and, as she walked ahead with her once purposeful stride she began to stumble and then fall down.’

A more sympathetic stock-taking of the decade highlights massive progress. While American scientists produced The Big Bang theory of creation, in Britain we experienced the explosion of a new cultural universe.

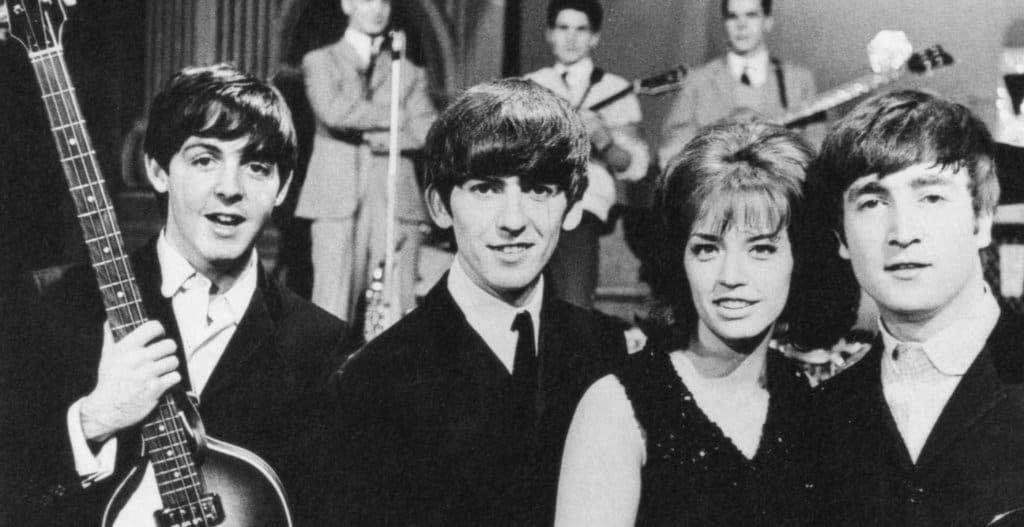

Music, dance and fashion were transformed by rock ‘n roll bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who and The Kinks. Teenagers, with more money and freedom than ever before, revelled in it. The number of boutiques, hair-dressers and night-clubs mushroomed in the big cities as Britain’s youth flexed its economic muscle.

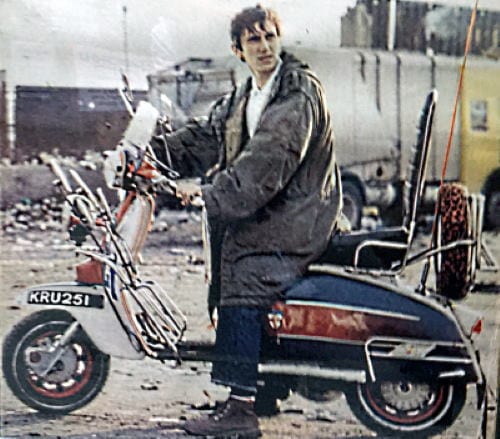

One of the most influential brigades in this progressive, un-conscripted army was The Mods, who emerged from a backdrop of improved living conditions. Rows of terraced houses still guarded the factories and warehouses, but the roofs were littered with TV aerials beaming in the latest goings-on in Coronation Street and the streets were lined with cars. Their musical roots lay in jazz and American blues circles, previously inhabited by the ‘beatniks’.

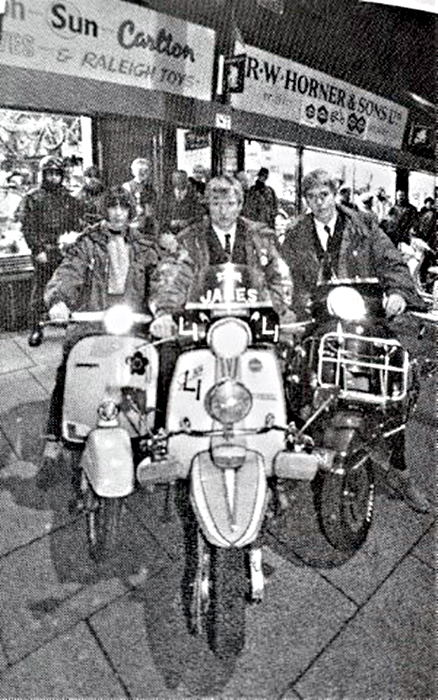

But Mods also enjoyed the style of Italy, speeding along on their scooters, Vespas and Lambrettas – the handlebars piled high with highly-polished wing mirrors – and tailor-made mohair suits, although the favourite item in a Mod’s wardrobe was a fish-tail Parka. They went to Turkish barbers for sharp, razored hair-cuts. Regular haunts were Kardomah coffee bars and city centre clubs, particularly in London and Manchester, where they could dance all night, enjoy live bands, and talk in a language of their own. A leading Mod was termed a ‘Face’, his lieutenants ‘Tickets’. A Brighton disc-jockey Alan Morris styled himself as King of the Mods, earning the title Ace Face – a role encored by Sting in ‘Quadrophenia’, a film made in 1979 but staged in 1964.

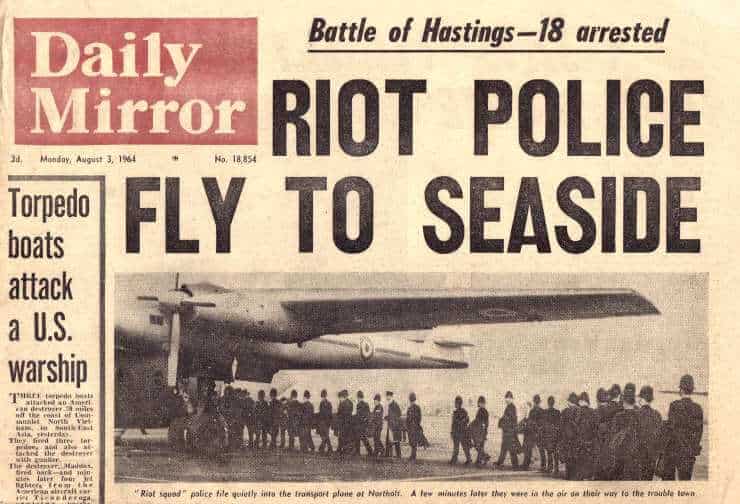

Unfortunately, they also developed a reputation for wild behaviour, drug-taking and drunkenness, exacerbated by a series of incidents in the mid 1960s when they fought with leather clad clans of motor-cyclists – Rockers – in southern resorts. The Mods and Rockers battles instigated a reaction which philosopher Stanley Cohen later disparaged as Britain’s ‘moral panic’.

However much of the criticism was exaggerated. Many of the clubs they frequented did not serve alcohol, only Coke and coffee. When, in the early hours of the morning, they staggered bleary-eyed into the street, it was through exhaustion having danced non-stop for hours, rather than through drink or drugs. Police in Manchester, exhorted by the Corporation’s Watch Committee to clean up the city before the 1966 World Cup matches at the Old Trafford stadium, raided a number of clubs to little effect.

Liverpool had The Cavern, famous for The Beatles, and London had a string of popular venues in and off Soho’s Wardour Street. But the Twisted Wheel in Manchester was the major Mods’ hub attracting coach-loads of teenagers from as far away as Newcastle and the capital. An inauspicious front door led into a series of dark rooms, a refreshments bar, and a small stage where Eric Clapton and Rod Stewart, among other up and coming stars, performed occasionally. Black artistes from the States were also welcomed, giving Manchester some kudos among American civil rights activists.

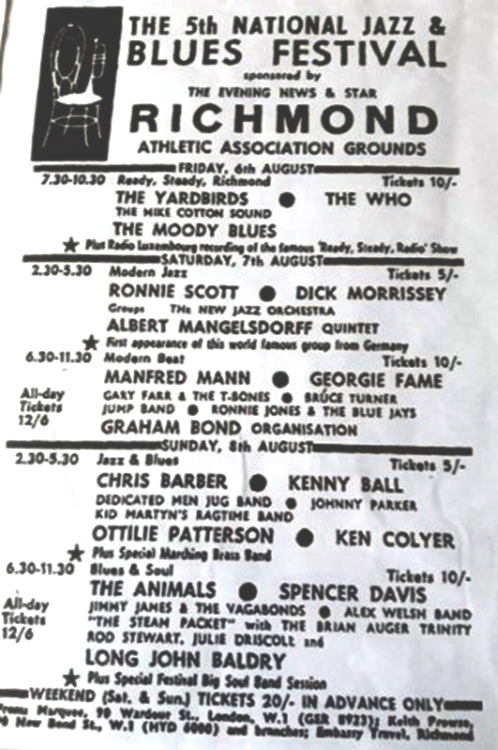

Until the mid 1960s there was no such thing as an annual rock festival. The National Jazz and Blues Festival staged at Richmond Athletic Recreation Ground came closest but in 1963 while retaining their title and some of the traditional musicians, headed by jazzmen Chris Barber and Johnny Dankworth, the organisers brought in The Rolling Stones (for a fee of £30) and gave them top billing the following year.

By 1965 the event leaned heavily towards rock with bands like The Who, The Yardbirds, Manfred Mann and The Animals. Thousands of Mods piled into Richmond for the three day event costing £1 for an all-in ticket. As there was no tented village, they camped out on the golf course and on the banks of the River Thames. A local newspaper labelled them as ‘people with a penchant for vagrancy and little use for all the conventional paraphernalia of beds, changes of clothing, soap, razors and so on’. Residents complained and the festival switched to Windsor in 1966 and then to Reading, but the Richmond finale was perhaps the apex of the original Mods movement and the forerunner of Glastonbury.

Poster advertising the Richmond festival 1965

Poster advertising the Richmond festival 1965

A wider Mod culture developed but was clearly distinct from the original. Scooters, razored hair and Parkas gave way to minis, shoulder-length locks, and Sergeant Pepper outfits. Flower Power and Psychodelia were the rage and, where at Richmond in 1965 The Who were accompanied by such as the Graham Bond Organisation and the Albert Mangelsdorff Quintet, in 1967 the Love In Festival at London’s Alexandra Palace (Ally Pally) drew massive crowds to watch Pink Floyd, The Nervous System and The Apostolic Intervention.

Street art also blossomed in that period. Avant-garde theatre groups shocked the more conservative sections of society but rapidly gained ground within the middle class. Over 7,000 turned up at London’s Albert Hall to listen to verse from both international and unknown poets. New magazines and small, radical theatres pulled together an affluent, well-educated mass of free thinkers from which emerged a number of left-wing political groups.

Eventually the Mods faded from view but they left a romantic image which is occasionally revived both in music and fashion.

Colin Evans was a teenager in the 1960s and launched his career in journalism in 1964 finishing as the cricket correspondent of the Manchester Evening News. He retired in 2006 and has since written of his Indian ancestry, and aspects of British history. Two of his books have been published, one about life in the mid 1960s and a biography of the cricketer Farokh Engineer. He has just completed a third book ‘No Pity’ investigating an unsolved murder in his home town in 1901.

Published: 12th July 2022