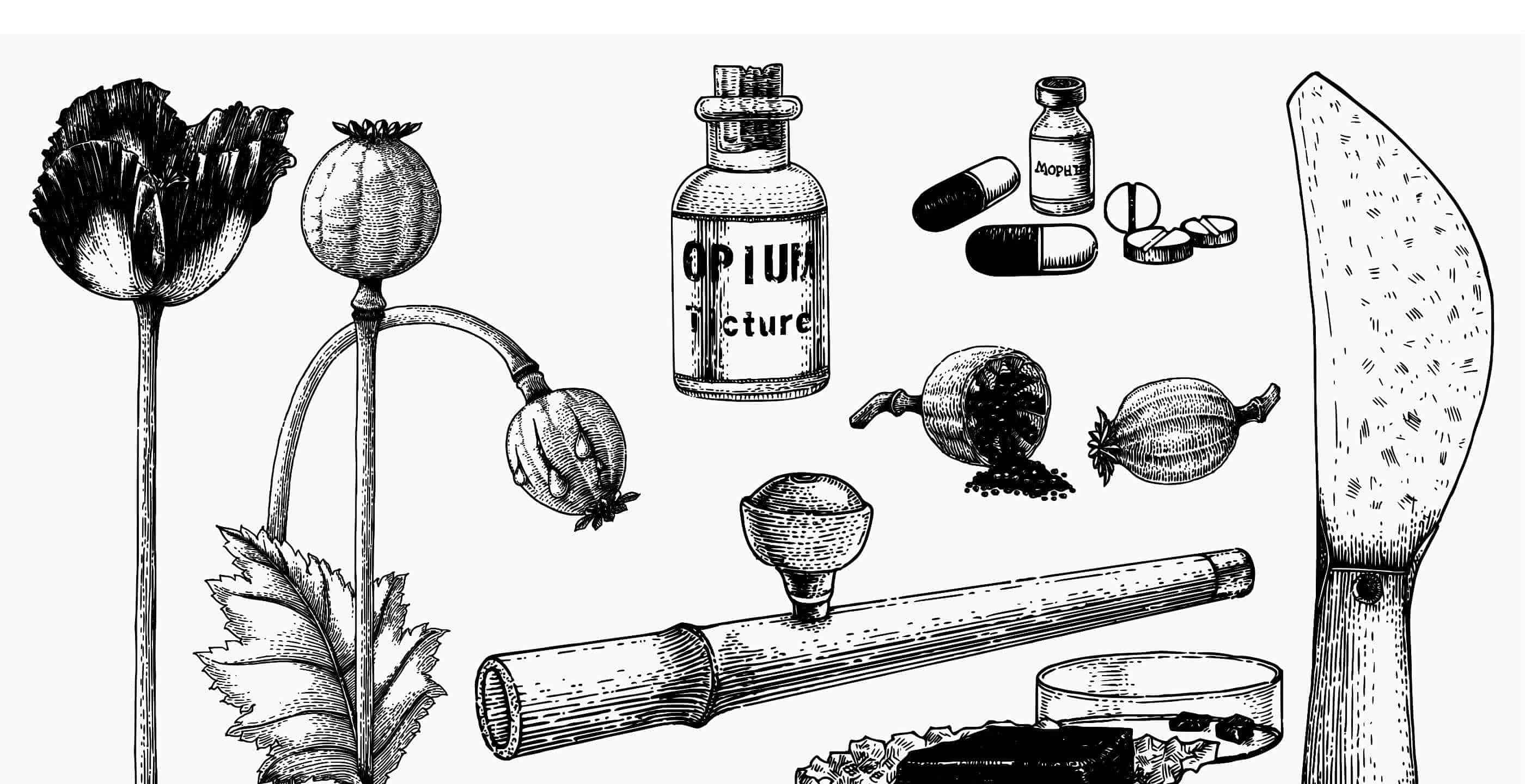

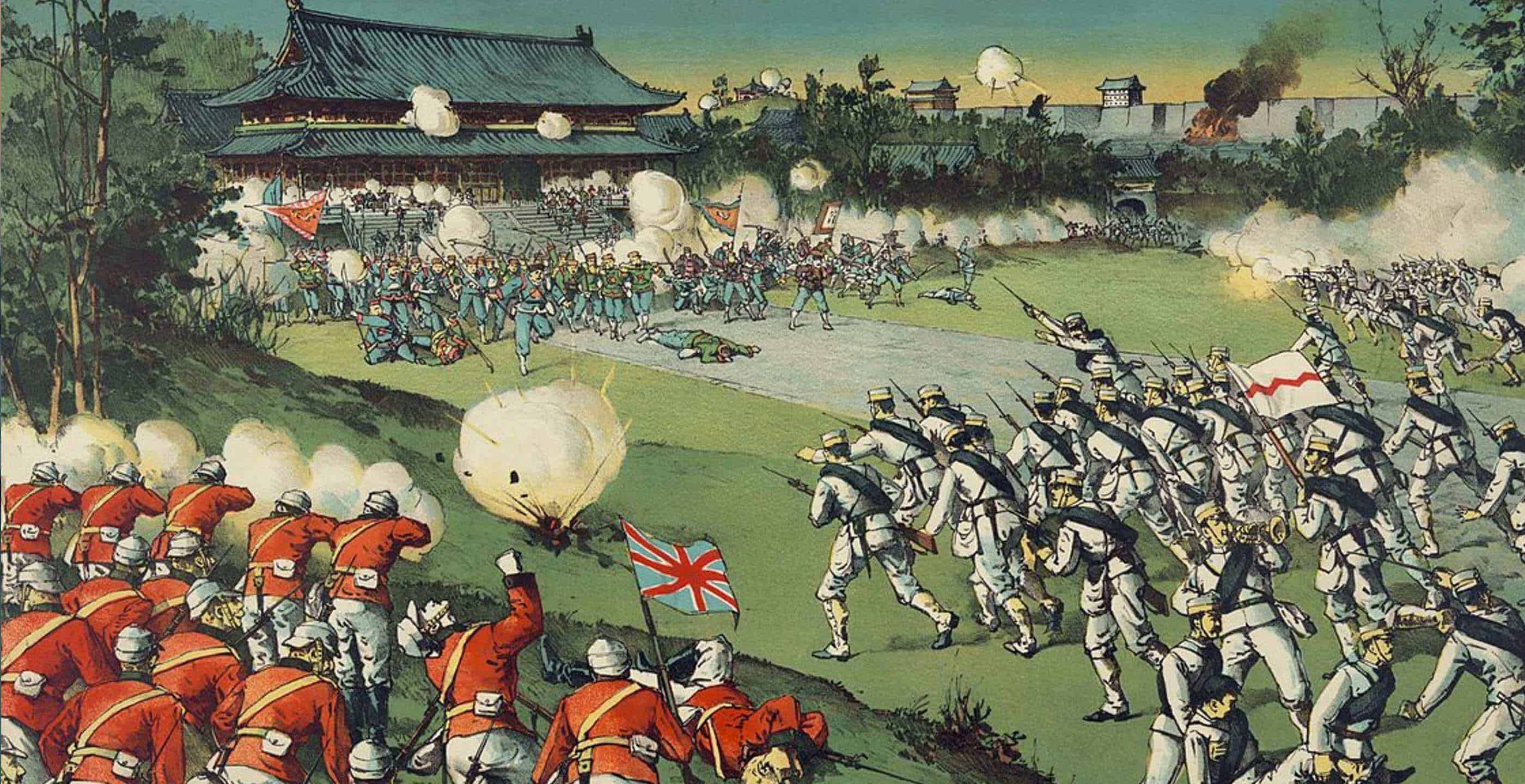

The number of female missionaries in China increased dramatically over the nineteenth century. However, these courageous women were not included in mission reports, contributing to them becoming “hidden from history”. One such woman, Mary Ann Aldersey, established the first school for girls in mainland China at Ningpo in 1843, a time when China was facing turmoil in the wake of their defeat in the First Opium War. Aldersey produced extensive accounts of her activities through correspondences with the London Missionary Society (LMS) and her personal diary. Her writings reveal her devotion, bravery and independence.

China presented British missionaries with a challenge, due to the segregation of Chinese society with women being kept mostly housebound and illiterate, resulting in a need for female missionaries to somehow engage with these women.

Aldersey’s Early Life

Aldersey was born on 24th June 1797 to a wealthy family in London. Aldersey gained her interest in China from her tutor, Robert Morrison, the first British missionary to translate the New Testament into Chinese.

Aldersey wanted to follow in Morrison’s footsteps but was prevented by her father for many years. However, she finally left for Java from Gravesend, Kent, on 10th August 1837 to work with Chinese communities on the island. She arrived on 2nd December 1837 and expressed in her diary “I had arrived on my dear parent’s wedding day, on the day of my arrival among the Chinese it was also my wedding day, I having been long betrothed myself to a people so interesting to me”.

She began by attempting to organise night schools for Chinese girls at Sourabaya, with little success and with much suspicion from the local Dutch authorities. However, she successfully converted two of her Chinese pupils, Christiana Ati and Ruth Kit, who became her lifelong friends and helpers.

Aldersey left Java for Hong Kong in 1841 and entered Ningpo after it had been captured by the British during the First Opium War. Ningpo became a treaty port in 1842 after the signing of the treaty of Nanking. Aldersey managed to secure premises for a boarding school for girls. However, many of the early students at the school were described as dull or diseased, with Chinese parents using the school to rid themselves of unwanted girls. The Ningpo residents accused Aldersey of attempting to sell their daughters as slaves, committing acts of torture or casting evils spells. Distraught mothers often entered the school demanding to see their children as they had heard that their children had been murdered.

Aldersey was determined to encourage girls to attend her school. In her letter to the LMS on 2nd December 1851, she asks for money to produce placards to advertise the weekly Saturday public service for Chinese women exclusively. Aldersey describes the methods used at the school in a letter to the LMS sent on 16th March 1854, to mark the tenth anniversary of the school. A typical week at the school was organised with students being educated in embroidery, learning the principles of the gospel twice a week, and attending service on the Sabbath. The school focused on supporting pupil’s understanding of Christian theology. Aldersey also implemented innovative educational technologies at her school; she introduced the Gospel of Luke embossed and supplied by the British and Foreign Bible Society to educate blind girls. Aldersey expressed her desire that these girls would pass on their learnings of the gospel onto the 200,000 people in China affected by blindness.

Aldersey maintained the school through her residence in Ningpo despite the attempts of local Mandarins to intimidate her. In her letter to the LMS on 12th November 1859, she detailed how rumours spread by wealthy Chinese men in local villages had prevented her from establishing a mission station, as the English residents of Ningpo were being accused of kidnapping Chinese people and selling them as “coolies”. She also complained in her diary on 25th October 1851 that a “madman” was being paid to follow and shout at her when she left the safety of her school house. On one occasion her house was attached by locals shouting “down with the foreign witch” over claims that Aldersey was attempting to harm an old women visiting the house. False accusations against Aldersey limited her ability to expand educational programmes to other areas of China. In her letter to the LMS for a £50 donation on 19th December 1856, she states that the difficulties she faced on a daily basis were too numerous to count, but that God provided her with sustenance to continue with her mission.

The school was a significant financial burden for Aldersey. For instance, on 2nd December 1851, she asked the LMS to increase their grant for the upkeep of the school from £50 to £80 (equivalent to £10,236 today). However, she faced bankruptcy and on 15th May 1854 she sent a letter to the directors of the LMS pleading them to send £50 to cover the cost of maintaining the school premises as she had limited funds. When reviewing the correspondence from Aldersey to the LMS between 1848-1859, the letters have a common theme emphasising how the school was a worthy investment in relation to the Protestant community in Ningpo in order to gain much needed financial support.

As time progressed, Aldersey became increasingly frail and she transferred the school to the American Presbyterian Society in 1860 when she resigned her position. She retired to South Australia to live out the rest of her days in a house named “Tsong Gyiaou” after a mission station. She died aged 71 in 1868.

The Significance of Aldersey

Aldersey expressed her independence as a female leader who was not managed by senior male missionaries in the field. She undertook ambitious activities to secure the future success of the school and faced potentially deadly challenges during her time in Ningpo. In this context, she was able to expand her influence within the public sphere and take on roles that would be impossible for her to achieve at home.

Aldersey accepted great risks in implementing female-focused missionary activity. In refusing to be intimidated by the challenges she faced, she set a positive example to other women that they too could make a significant contribution to the development of female education. It is ironic that Aldersley was able to demonstrate the strength of female endeavour in China where the position of females was very subservient to men. The lack of material on female missionaries has resulted in a masculinised version of reality which is both biased and false. Female missionaries and their stories are fundamental to understanding nineteenth century missionary activity and their self-sacrifice, determination and ingenuity should not be forgotten in favour of a conformist idea of nineteenth century British history.

By Luke McKelvey BA (Hons) International Relations & History, MA Globalisation & Development. Special interest in archival research focusing on forgotten historical figures and has a keen interest in Global History. Luke works as a development officer for a charitable organisation but is considering opportunities for future research.