Save our Stories: Their Finest Hour

A project entitled Their Finest Hour is currently underway to establish a national archive of memories and mementoes from the Second World War, with the support of a grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Oxford University, which runs the project, has launched a campaign entitled SOS Save Our Stories, calling for contributions which will be preserved in digital form, as a resource for future generations.

The kind of keepsakes that make valuable additions to the digital collection include army service records, photographs, ration books and identity cards, which many families may have stored away somewhere in a box, a cupboard, or in the attic.

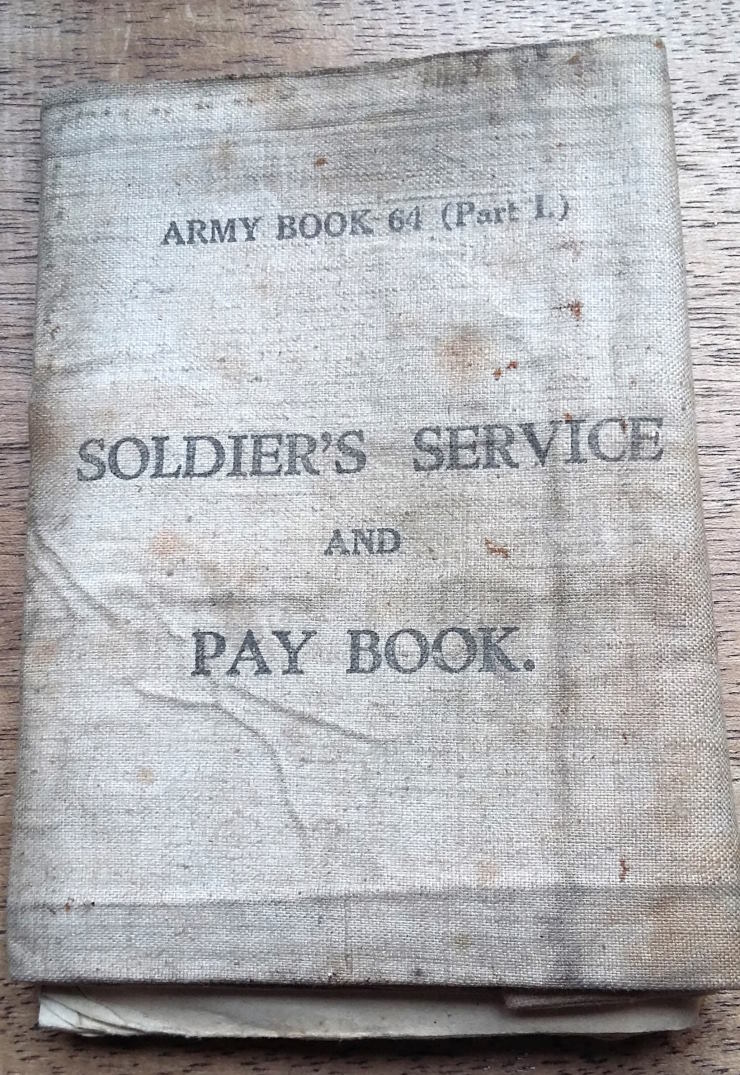

Two generations of my family kept their most treasured heirlooms in a small tin casket, which contains black and white photos, certificates of birth, marriage, and death, and other important documents. Among them is a faded booklet entitled Army Book 64, a service record and pay book issued to British Army soldiers towards the end of the Second World War, listing details of when and where the soldier was enlisted and subsequently stationed.

The booklet was issued to my father, Robert George Smith, known to friends and family as Bob, who was enlisted in Scarborough, Yorkshire, in 1941 and was later stationed in Bangalore, southern India, in 1944. His medical records list vaccinations against Tetanus, Typhoid and The Plague. The back page of the booklet was left blank – this was intended as a space which could be used to write a will.

Of the few memories Bob shared from his army days, the one that made the biggest impression on him was from his posting in India, when he once caught a glimpse of a distant tiger prowling at sunset. He also spent time in Lebanon, which he said was, at the time, a beautiful, unspoilt place.

One of his more entertaining anecdotes was about the time he buried a tin of corned beef in the desert. When he opened the can of army rations, the meat had melted in the heat. He couldn’t bring himself to eat it, so he dug a hole and hid it in the sand.

My father lost friends on the front line, but he never spoke about that. Most men of his generation were brought up to believe that it was unmanly to shed a tear or admit to feeling fear. Whatever happened, it was chin up, bunker down, as men went to the battle front without question or complaint, while back at home their families faced bombing, rationing, and sometimes evacuation, with stoicism and determination.

This community spirit was robustly encouraged by wartime posters urging everyone to “Keep calm and carry on!” The slogan chosen for this project – “Our finest hour” was attributed to the wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill. If Bob had any uncomfortable emotions arising from his wartime experiences, he was good at burying them – in the same way that he buried his beef in the sand.

Please click here for more details on this campaign and how to submit your stories.

By Angela Lord. Angela Lord is a freelance writer based in Surrey. She studied Modern Languages at university, trained as a newspaper journalist and has a particular interest in the English language and its history. Currently writing on arts, culture and travel.