The Highland Clearances remain a controversial period in Scotland’s history and are still talked of with great bitterness, particularly by those families who were dispossessed of their land and even, to a large extent, of their culture, over the period of around 100 years between the mid 18th and 19th centuries. It is still considered a stain on the history of the Scottish people and is also a main contributing factor for the relatively enormous world-wide Scottish diaspora.

By the mid 1800s there was a tangible North-South divide within Scotland. There was an idea of the Highland culture and way of life being ‘backward’ and ‘old-fashioned’, out of step with the rest of Scotland and the recently United Kingdom. Those people in the south now identified more with their southern counterparts than with the old clan culture of the highlands and islands. Southern Scots saw themselves as more modern and progressive, with more in common in language and culture with their southern, English neighbours.

However the Highland culture, ancient and proud, was fiercely independent and rooted in incredibly important traditions of family and fealty. The clans such as Macintosh, Campbell and Grant had ruled their lands in the highlands for hundreds of years. The Highland Clearances changed all that however, and altered a distinct and autonomous way of life. The reasons for the highland clearances essentially came down to two things: money and loyalty.

Loyalty

As early as the reign of James VI in Scotland, cracks were beginning to appear in the clan way of life. When James ascended the throne of England in 1603, he moved south to Westminster and ruled Scotland from there, only visiting the nation of his birth once more before he died. James was a suspicious king (his distaste for witches has already been noted!) and did not completely trust the clan leaders in Scotland to rule without his supervision. He feared opposition and plotting. Although to be fair to James it was this canniness that led him to foil the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, although of course the threat there did not come from Scotland. In order to better maintain control of the North and to prevent the clan chiefs from superseding his power with their people, James kept the chiefs away from their clans for extended periods, requiring them to do duties that kept them away from their people. This was to ensure that the peoples’ allegiance remained to their King and not to their clan Chief.

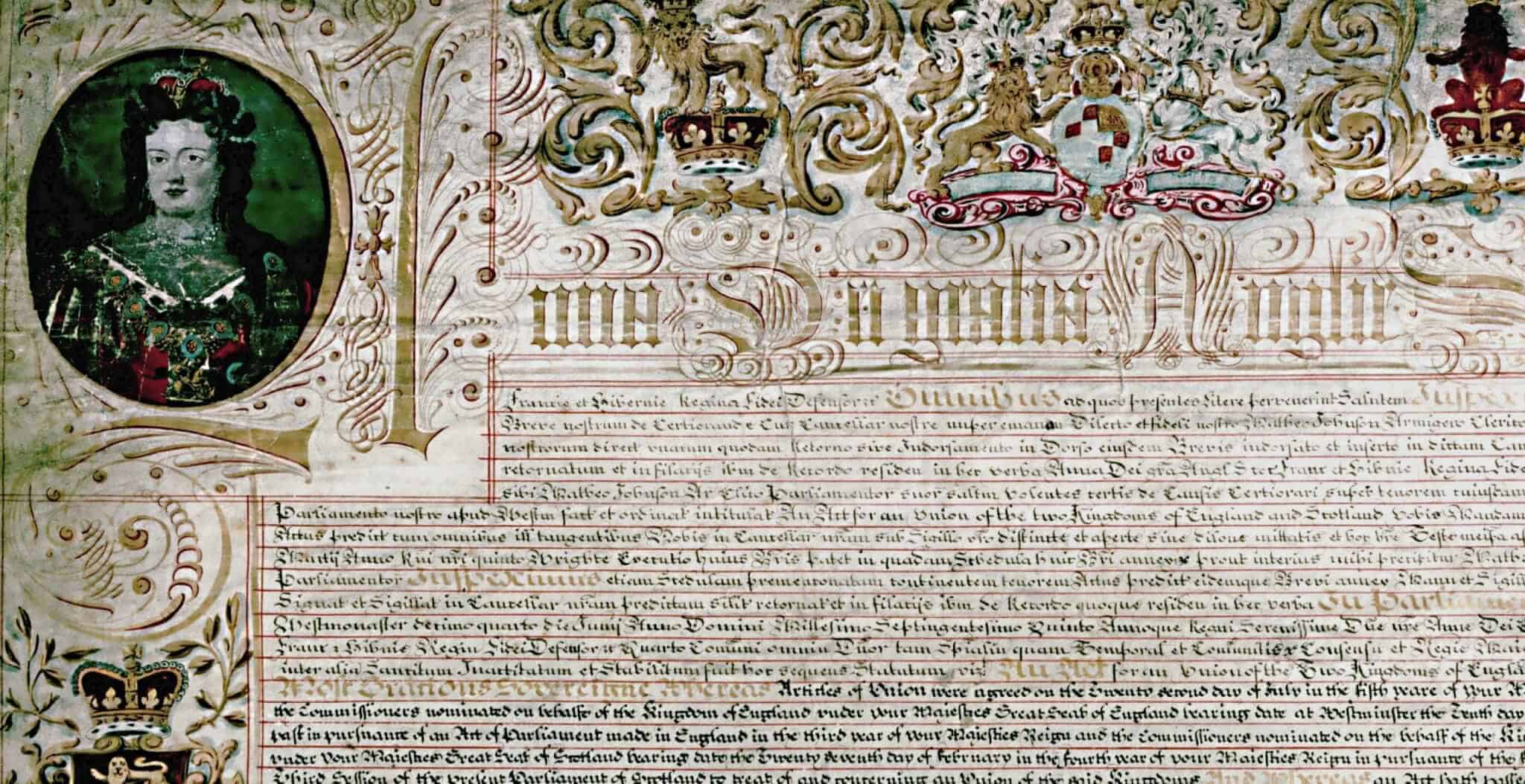

Things worsened for the clans after the Glorious Revolution of 1688-9 when the Stuarts were replaced by William of Orange and the Hanoverian dynasty. There were many Scots still fiercely loyal to the Stuart monarch, and this led to several Jacobite uprisings in support of Prince Charles Edward Stewart, or ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, who was James VII’s grandson. The Jacobites wanted to oust what they saw as an illegitimate ruler and reinstate the Stuart king. There were several rebellions with this as the intended outcome, and there was a swell of support for the Jacobite movement in the highlands. This was further fostered in many ways by the Act of Union of 1707: many Scots felt betrayed by this and there was widespread opposition to the joining with England. This led to further support for a return of the Stuart monarchy and by consequence, the Jacobite rebellions.

From 1725 onwards, garrisons manned by English soldiers or ‘redcoats’ sprung up all over the Scottish Highlands, notably at Fort William and Inverness. These were to suppress Scottish opposition to the King and to remind the highland clans that they were subject to English rule.

The final and bloodiest rebellion was led by Bonnie Prince Charlie himself in 1745 and it culminated in the slaughter at Culloden in 1746. The Jacobites faced the English redcoats on an open field and were almost annihilated. They were no match for the might of the English army and the losses suffered by the highlanders were catastrophic. The Jacobites were around 6,000 strong whereas the English numbered around 9,000. Of the 6,000 Jacobites, 1,000 are thought to have died, although the exact number is unknown. Many of those who died were clansmen; some tried to escape but were hunted through the countryside and slaughtered. Some prisoners were taken to London where around 80 were executed, including the last man to be beheaded in Britain, Lord Lovat, Clan Chief of Fraser. He was beheaded at the Tower of London in 1747 for high treason for his part in supporting the Jacobite rebellion. The Battle of Culloden was to be the swan-song of Highland Clan culture, the last stand of a way of life that had existed for centuries.

What happened after Culloden?

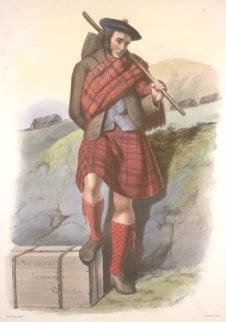

After the initial swift and bloodthirsty retribution for the Jacobite rebellions, laws were instigated to prevent any further groundswell of support for the previous monarchs. In 1747 ‘The Act of Proscription’ was passed. Clan tartan had become popular during the Jacobite years and this was outlawed under this new act, as were bagpipes and the teaching of Gaelic. The Act was a direct attack on the highland culture and way of life, and attempted to eradicate it from a modern and Hanoverian-loyal Scotland. Acts such as this, intended to wipe out an ancient culture, have given modern Scotland an unusual ally and kindred spirit in the Catalans. Cataluña is in the North East of Spain, the capital of which is Barcelona. They have their own culture and language (Catalan) that is completely distinct from Castilian Spain. In 1707 Scotland lost the right to self-rule, and the Catalans lost the same to the Spanish a mere 7 years later in 1714. Although these two countries are thousands of miles and cultures apart, they have an unusually similar shared history of oppression. Once Franco had won the Spanish Civil War in 1939, he treated the Catalans in much the same way the Highlanders were treated after Culloden. Franco outlawed the Catalan language and made the Catalans subject to Spanish rule. Today the Catalans watch the issue of Scottish independence with great interest.

Money

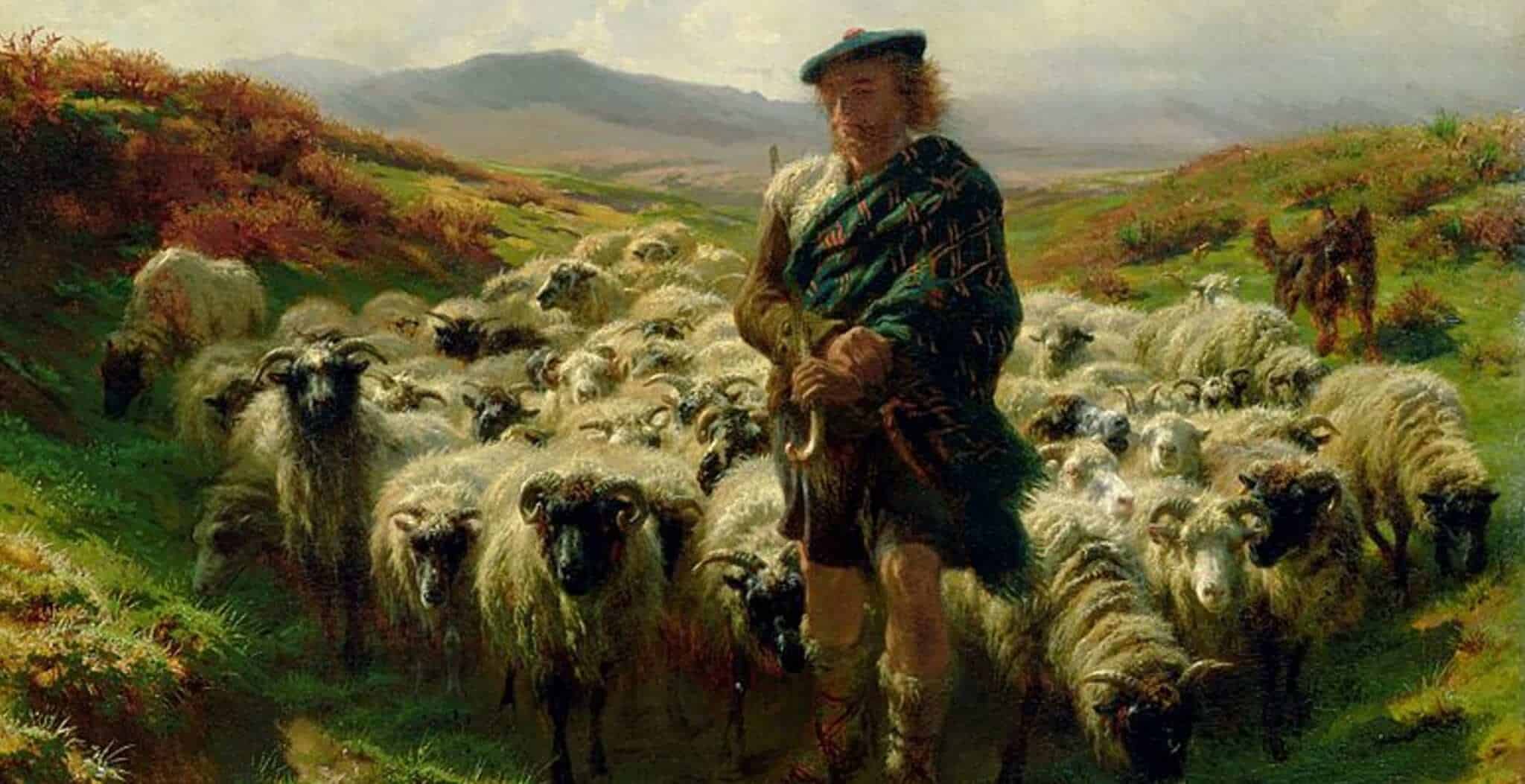

It was not only highland culture that disappeared over this period but also the highlanders themselves, for the most prosaic of reasons: money. It was deduced by those landowners on whose lands the clans lived and worked, that sheep were exponentially more financially productive than people. The wool trade had begun to boom and there was literally more value in sheep than people. So, what followed was an organized and intentional removal of the population from the area. In 1747, another Act was passed, the ‘Heritable Jurisdictions Act’, which stated that anyone who did not submit to English rule automatically forfeited their land: bend the knee or surrender your birth right.

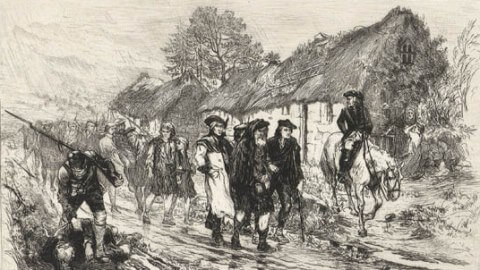

Some highlander clans and families had lived in the same cottages for 500 years and then, just like that, they were gone. People were literally turned out of their cottages into the surrounding countryside. Many were relocated to the coast where they would subsist farm almost cultivatable land, supplementing themselves by smelting kelp and fishing. However the kelp industry also began to decline. Some were put on to different land to farm crops, but they had no legal rights to the land. It was a very feudal arrangement. Many highlanders chose to emigrate but some were actually sold as indentured slaves.

Things began to deteriorate even further in the 1840s. The potato blight and the subsequent potato famine rendered the already difficult lives of these resettled crofters almost untenable. It has been said that at the height of the clearances as many as 2,000 crofter cottages were burned each day, although exact figures are hard to come by. Cottages were burned to make them uninhabitable, to ensure the people never tried to return once the sheep had been moved in.

Between 1811 and 1821, around 15,000 people were removed from land owned by the Duchess of Sutherland and her husband the Marquis of Stafford to make room for 200,000 sheep. Some of those turned out had literally nowhere else to go; many were old and infirm and so starved or froze to death, left to the mercy of the elements. In 1814 two elderly people who did not get out of their cottage in time were burned alive in Strathnaver. In 1826, the Isle of Rum was cleared of its tenants who were paid to go to Canada, travelling on the ship ‘James’ to dock at Halifax. Unfortunately, every one of the passengers had contracted typhus by the time they arrived in Canada. This ‘transportation’ was not that uncommon, as it was often cheaper for landowners to pay for passage to the New World than to try and find their tenants other land or keep them from starvation. However, it was not always voluntary. In 1851, 1500 tenants in Barra were tricked to a meeting about land rents; they were then overpowered, tied up and forced onto a ship to America.

This clearing of the population is a main contributor to the massive world-wide Scottish diaspora and why so many Americans and Canadians can trace their ancestry to the proud, ancient clans of Scotland. It is not known exactly how many highlanders emigrated, voluntarily or otherwise, at this time but estimates put it at about 70,000. Whatever the exact figure, it was enough to change the character and culture of the Scottish Highlands forever.

A 17th century Scottish prophet known as The Brahan Seer once wrote,

The big sheep will overrun the country till they meet the northern sea . . . in the end, old men shall return from new lands.”

It turns out, he was right.

By Ms. Terry Stewart, Freelance Writer.

Published: June 2, 2017.