“It was in Spain that [my generation] learned that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own recompense. It is this, doubtless, which explains why so many, the world over, feel the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy.” – Albert Camus

Why include a Civil War that happened in Spain in the 1930s, in a magazine about the history of the UK you might ask? Well, the reasons are many and manifold.

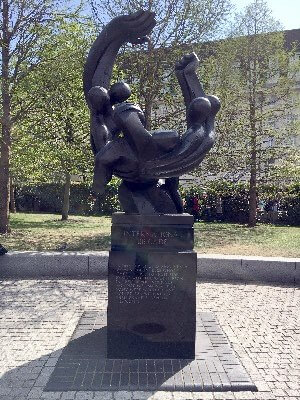

What happened in Spain can be seen all over Britain today. There are memorials commemorating those brave Brits who went to fight literally scattered all around the country, from Glasgow and Dundee to London and Southampton. These memorials exist because in the 1930s, even though it was illegal to do so, many courageous and determined British volunteers went to Spain to defend democracy and decency and fight against Fascism during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39.

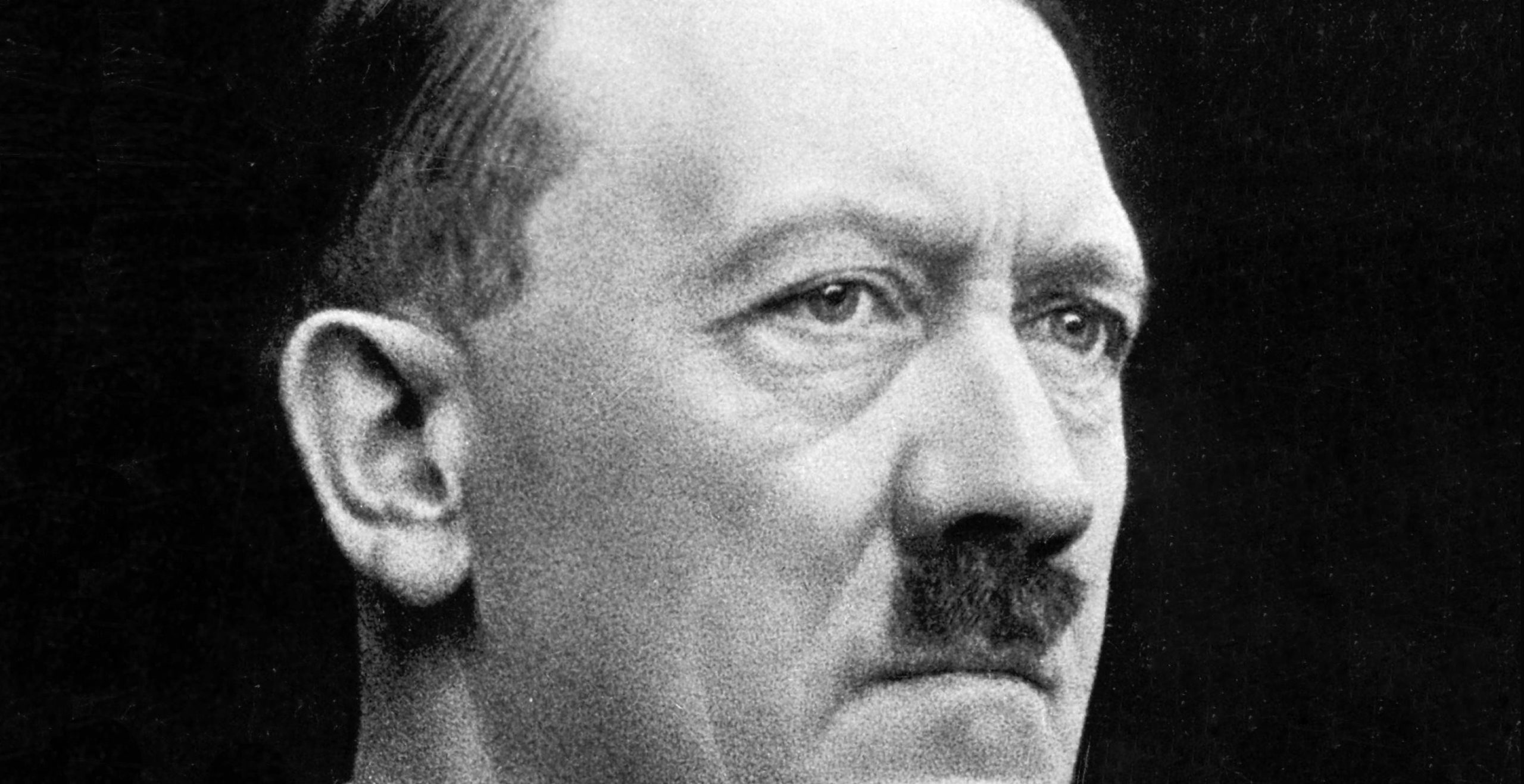

A force of Nationalists (later referred to as Fascists) lead by the Fascist General Francisco Franco, overthrew the legal and democratically elected Republican Government of Spain in a military coup, starting a struggle that was to last for three years. It progressed almost immediately from a ‘civil war’ to a ‘total war’, with Hitler and Mussolini aiding Franco and the Nationalists and individuals from all over the world coming to the aid of the Republic.

Britain and France quickly opted for a position of non-intervention, in theory if less so in practice. The struggle raged back and forth across Spain and became a focus for the eyes of the world, partly because it was seen as a proxy war and the fate of the entire world seemed to be inexorably linked to the outcome in Spain. Indeed, many British people from Aberdeen, to Manchester, Cardiff to London could already see this.

During the late 1930’s Britain was going through a recession, the tail end of the depression brought with it mass-unemployment, hunger marches and widespread discontent. Many British people felt a deep sympathy for the position of the Spanish peasants who were also struggling. Some saw their fight against Fascism and for a better life as a class struggle, international and not only specific to Spain. It is perhaps unsurprising therefore that so many Brits took up the struggle with Spain and went to fight Fascism in the International Brigades.

Jimmy Maley was one of these people. He went from Glasgow straight into the bloodiest battle of the Spanish Civil War at Jarama where around 10,000 died, including almost 150 from the International Brigades. Then he was taken to a Spanish prison. His experiences were the basis of the play, ‘From the Calton to Catalonia’.

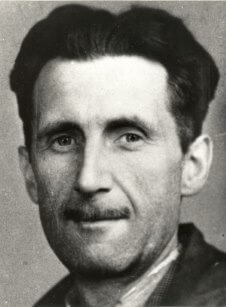

Many famous Brits also went to fight in Spain: W. H Auden, originally from York, George Orwell, Tom Wintringham from Grimsby and of course John Cornford who went from Cambridge to fight Franco’s Fascists and gave his life in Spain. Although it became known as a poets and intellectuals war due to the seemingly disproportionate number of poets and writers that actually volunteered to fight, around 95% of those who joined the International Brigades from Britain were from working class backgrounds.

Although it may have been a foreign war they were fighting for ideals that were also British: freedom, democracy, tolerance. This was a chance to fight for freedom and equality for the masses where it could make a tangible difference. Conditions in Britain in the 1930s were undoubtedly bad, but not as nearly as bad as in Spain. It also offended many that it was a legal and legitimate government that had been overthrown by a military rising.

The reasons these individuals went were diverse whether political or moral. However, as C.D Lewis wrote in his 1938 poem ‘Volunteer’, ‘we came because our open eyes could see no other way’. Out of 40,000 International Volunteers from 53 countries, including as far away as America (Hemmingway fought in the International Brigades himself) who went to fight in Spain, 2,100 were British, 500 were Scottish (half of which were from Glasgow) and 63 volunteers that went to fight from Manchester of whom 18 were killed in Spain. Of those brave 2,100, 534 (that figure changes depending on which memorial you are looking at but it was around 530) would never return to Britain alive.

It was not only the International brigades that linked Spain with the UK however. There was also Guernica.

“On Guernica loosed their venom,

Hammered helpless men and women

Into pulped and writhing earth.

Thus they brought the blitz to birth.”

-George Steer (War correspondent)

On 29 April 1937, a massive force of German Junker planes, Heinkel and Messershmitt fighters that made up Hitler’s Condor Legion, bombed and machine gunned Guernica at around 4.30pm on market day. Guernica was the cultural heartland of the Basque people, and at that time it was busy with women, children, stalls, and animals. Incendiary bombs were used which burst into flame on impact. The town was absolutely destroyed.

Report after report flooded into Britain, many telling the official and untrue story of ‘red-atrocities’ in the town of Guernica, the torching and destruction of a town by ‘red’ (or communist) insurgents. However, British journalists and experienced war correspondents who witnessed the German attack also sent dispatches back to Britain, telling what really happened in the town that day. Christopher Holme wrote, ‘The world ended tonight [the people] Are scratching for fragments of their slaughtered world.’

The effect of this reporting was immediate: the bombing of Guernica became the most vilified and hated event of the Spanish Civil War: it crystallised the forces of ‘good’ against ‘evil’ in many people’s minds. The reports continued. Monks was the first British correspondent on the scene: his article, ‘Guernica destroyed by German planes’, told of a wilful atrocity. “Most of Guernica’s streets began or ended at the Plaza. It was impossible to go down many of them because they were walls of flame. Debris was piled high.” George Steer told a similar story, “Out of the hills we saw Guernica itself. A meccano framework. At every window piercing eyes of fire, where very roof had stood wild trailing locks of fire.”

The sheer scale of the bombing shocked many, but the deaths of the many women and children shocked more. The involvement of the German Condor legions also left many with a sense of foreboding. However, it was the reporting that touched the hearts of those in Britain, so much so that the government agreed to offer shelter to Basque refugee children, their first foray away from non-intervention. And on 23 May the first Basque children arrived in Southampton. There is a plaque commemorating this even to this day.

Guernica, by Pablo Picasso, 1937.

Couple this with the opening of the World Exhibition in Paris on 25 May 1937 showing Picasso’s Guernica, and it is unsurprising that the sympathy with the Basque refugees developed in Britain the way it did. Many of the British public made the trip to see Guernica, but many more saw prints and heard about it on news broadcasts. It became the most political and controversial of Picasso’s works. A huge canvas in stark black and white, which solidified the ‘right’ versus ‘wrong’ idea already seeded in people’s minds, it shows a tangle of mutilated animals, people and debris, most famously a woman holding a dead child to her breast. This was probably the best public relations episode that the Left had during the Spanish Civil War. It corresponded with the reports of debris, flames, destruction and bombs, and together with Basque refugees in Southampton, it epitomised the atrocities being committed and the evil of the Fascists.

The atrocity of Guernica only solidified in the minds of those watching in Britain and those International Brigaders that were already fighting, what could happen to their own countries if Fascism was allowed to triumph. The involvement of the International Brigades and the arrival of the Basque children in Southampton are two aspects of the story that show the inextricable links between a Spanish fight that was taken up by those brave British souls, whose open eyes really could see no other way.

“He gives but he has all to give

He watches not for Spain alone,

Beyond him stand the homes of Spain

Behind him stands his home.”

– Miles Tomalin

By Ms. Terry Stewart, Freelance Writer.